The Magic Number

An Interview with Margaret Randall

by Lee Rossi

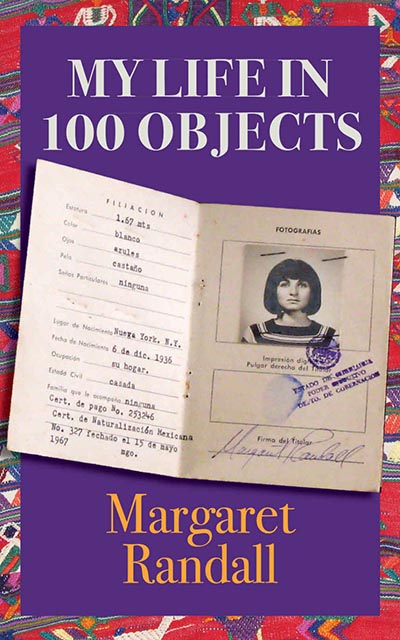

MARGARET RANDALL, POET AND ACTIVIST, is the author of 150 books. For twenty-five years she lived in Latin America, first in Mexico, then Cuba, and finally Nicaragua, before returning to the United States. Deemed a "subversive," she fought a five-year battle to regain her U.S. citizenship. While in Latin America she raised four children and worked a variety of jobs, always finding time to participate in the literary and political struggles of her host countries. In Mexico she edited and published an important bi-lingual literary magazine, El Corno Emplumado/The Plumed Horn. Her most popular book is Sandino's Daughters, a series of conversations with Nicaraguan women revolutionaries about their struggles in overthrowing the dictator Somoza. Now in her eighties, she remains incredibly active and engaged. In 2020, she published a book of pandemic poems; translations of Latin American poetry and memoir; a volume of Ecuadorian poetry, which she selected and translated; and two memoirs, one about her life as a poet, feminist and revolutionary and the other, My Life In 100 Objects, a multi-disciplinary work featuring her photographs as well as her writing. The following exchange occurred in December 2020, via email.

Poetry Flash: It's a great honor to speak with you. You've had a long, adventurous life, and during that whole time you've been committed not just to the art of poetry but to the spread of democratic ideals.

One of the things I like about your new book, My Life in 100 Objects, is the way it summarizes the various aspects of your "one wild and precious life." How did you happen upon this format, which is basically a guided tour of your bookshelves and walls, your photo albums, jewelry case, and possibly your attic? What do you want to tell your reader about your life and about you are as a person?

Margaret Randall: I got the idea for My Life in 100 Objects from reading a book called The World In 100 Objects by Neil MacGregor, curator of The British Museum. He chose one hundred objects in the museum's collection, pieces from all over the world, and wrote text that accompanied the photographs. The oldest was a two-million-year-old chopping tool from the Olduvai Gorge, the most recent a credit card. That book, which came out in 2010, fascinated me. I wondered what objects I would choose to exemplify my life. I decided to find out by writing my book.

PF: The objects in your book are natural, archaeological, artistic but almost never products of industrial capitalism. How did you choose the objects in your book? Was it mainly emotional, political, intellectual, spiritual, or some combination? How long did it take you to come up with the final list? Why a hundred, is that a magic number?

Randall: Well, some of them are products of industrial capitalism, such as my first camera, first typewriter, and the treadmill on which I exercise. But you're right, most are not. I didn't plan it that way, but I suppose I am someone who is more readily drawn to natural, archaeological or artistic objects. I am also old enough to mourn the loss of so many artisanal or handmade things. I chose the objects in my book because they are meaningful to me, and because I still possess and therefore was able to photograph them. I'm sure I was emotionally as well as intellectually inspired. I can't remember how long it took me to come up with the final list. One hundred is not magical in my mind but seemed like a manageable number. As I say in my introduction, I could have chosen fewer or more. Maybe I was following MacNeil's example.

PF:Places are important to you, especially places which remind us human beings of how little we are. Could you talk a bit about your attraction to sites like the Burr Trail in Utah, or Arizona's Canyon X, or Petra and Wadi Rum in Jordan? How does your feeling for those places influence your social and political concerns?

Randall: Place is very important to me. The landscape of the U.S. American Southwest lives in my poetry as well as in my photography and my heart. I grew up with those red rocks, slot canyons, changing shadows and vast skies. And I have been fortunate to be able to travel and visit other places that have moved me in similar or other ways. I'm also intensely attracted to ancient ruins, those places left by peoples and cultures that went before. I think people in every era have basically had the same concerns: how to live peacefully, feed themselves and their children, tell their stories and create meaning. So, although they may look different today, and although we as a people have pushed our resources to the limit—something those who lived in earlier times rarely had to consider—I don't believe our social and political concerns are all that different. When I visit ancient sites, such as Petra in Jordan or ruins right here in the Southwest, I hear the whispered voices of ancestors and imagine how they confronted the problems of their lives.

PF:Thinking about your poetry and work as a social activist, I'd compare you to writers like Carolyn Forché or Adrienne Rich. Do you think those are fair comparisons? Who do you consider your most important role models and mentors?

Randall: I think those are apt comparisons. Adrienne Rich and Carolyn Forché are both writers I admire greatly. Also, César Vallejo, Juan Gelman, Audre Lorde, June Jordan, and many others. In terms of mentorship, though, I have been fortunate to have had important mentors in different fields. The first may have been the painter Elaine de Kooning. The Cuban revolutionary Haydée Santamaría was another. The Salvadoran revolutionary and poet Roque Dalton. And the South African novelist Mark Behr. By mentor, I mean someone who modeled a way of being, a talent and courage that has affected my life and work in an ongoing way. I also consider my wife Barbara a mentor, and my children, grandchildren and great grandchildren. They teach me things every day.

PF:Throughout the new book you give evidence of your affinity with the poets of the Beat movement. There's a tribute, for instance, to Lawrence Ferlinghetti's City Lights bookstore in San Francisco, a place dear to many, and a wonderful description of a latter-day gathering of Beats and neo-Beats in New York City in 2016. Then there's an anecdote in your 2009 memoir, To Change the World, about driving from Santa Fe to San Francisco in hopes of meeting Allen Ginsberg, a meeting which never happened. What drew you to the Beats, and what characteristics of their work do you emulate or employ in your own poetry?

Randall: I was part of the Beat movement, though somewhat younger than its principal exponents and on the periphery. I probably didn't identify with them as much at the time as I have since; looking back sometimes offers a perspective one doesn't have at the moment. When I heard Ginsberg's "Howl" read out loud at a party in New Mexico in 1956, it changed my relationship to poetry. Prior to that, I hadn't felt much connection. Poetry was taught poorly by my public school teachers, and I hadn't been able to relate. Ginsberg's poem railed against the social hypocrisy I also felt, especially as a young woman coming up in the stifling 1950s. My life and Ginsberg's had little in common, but I was deeply moved by his rejection of a suffocating status quo. And I knew those poets. In New York City many of them were my neighbors and friends. I was also influenced at the time by other poetic tendencies: Deep Image and Black Mountain, to name two. All these movements emphasized authenticity, though, and I don't think my poetry emulates theirs. I prefer to believe that I have developed a voice of my own.

PF:You write in 100 Objects: "The Beats keep on changing America, not only its literary culture but its way of looking at the world." Can you identify for us some of the changes in American culture that you associate with the Beats?

Randall: Well, Allen Ginsberg was one of the first writers of my generation who was openly gay and advocated for gender equality. Calling issues by their names, not ignoring or hiding them is also something I associate with the Beats. I think we look at the world more honestly today in large part because poetry and art have lifted veils of subterfuge and secrecy.

PF:In the chapter entitled, "Book Bag from City Lights," you talk about the obscenity trial of Allen Ginsberg's poem "Howl," an early favorite of yours. I love the fact that you give the names of the Collector of Customs, Chester MacPhee, who leveled the original charge of obscenity, and of the bookstore manager, Shigeyoshi Murao, who was arrested on charges of selling obscene material. In one sense, giving those names reflects your experience as a journalist, but it also indicates something important about the culture wars we've been living through for over fifty years now, the implicit racism of a white Anglo accusing and a non-white non-European being arrested. Any comment?

Randall: Clearly, in that particular instance the issue of being Anglo or non-Anglo was circumstantial, because Ferlinghetti was also being charged and it's quite possible that various races were involved, on both sides. But your question gets at something important. I've long believed it is important to name names, identify victims and victimizers not generally but by their names. I think it encourages accountability. It's also just interesting in terms of creating a fuller picture. It's always more interesting to say an oak or palm tree rather than a tree.

PF:Writing about your recent memoir, I Never Left Home: Poet, Feminist, Revolutionary,you remark that the sixties "have been misrepresented by most of those who have written about them." What do those other writers get wrong? Does anybody get it right?

Randall: I think the sixties was a vibrant, courageous and important time in our history, and I think many who have written about that time have intentionally misrepresented it; there are many people who are frightened that we'll have another period like it. It's not that I don't think some writers have gotten it right. Susan Sherman's America's Child is a book that rings absolutely true and has never gotten the recognition it deserves. And there are others. But what I often feel when I read about the sixties is that the writer doesn't give us an in-depth picture of what those years really felt like. Why did we react the way we reacted? Why did we do what we did? I get the feeling that great protests such as the one against the U.S. American war in Vietnam are described without describing what that war was like, why we took to the streets the way we did. But yes, I do think some people have gotten it right. And hopefully more will.

PF:In the last ten years, especially, we've seen a growing democratization of poetry. Since 2010, it's become routine for poets of color to win our most prestigious prizes and awards. One also notes the many prize-winning LGBTQ+ poets who have contributed their voices to the current cultural scene. I think that's a good thing. I hope it will last. Of course, there are any number of religious and cultural conservatives who would like to put the genie back in the bottle. What do you see in America's future; will we finally become a multi-racial, egalitarian democracy, or will we return to a "Whites Only" settler-colonial paradise?

Randall: This is an important question. Sometimes writers of color or LGBTQ+ writers are published because their voices are powerful, and—as with all such issues—sometimes because it is a passing fad from which a publisher hopes to make money. Of course, I hope that America's and the world's future is more egalitarian, more democratic and more recognizing of the fact that we are a multi-racial and multi-gender civilization. But I fear that four years of Trump has done tremendous damage. One of his most frightening legacies, I think, has been to give permission to expressions of prejudice and hate. We can see this in everything from language to terrorist acts. Sadly, the open inclusive society and the colonial settler "paradise" aren't separate. They inhabit the same world, ours. So exclusion and bigotry continue to infect us, and we must continue to struggle for a healthier world.

PF:At the moment we get frequent reports about infighting in the Democratic Party between moderates and progressives. Something similar has been happening in the world of culture. How do you view the controversies over what's called 'cultural appropriation.' Is it okay for a white painter to represent a brutalized Emmett Till in his coffin or not? Is it okay for a white male poet to impersonate a black sharecropper? What boundaries, what intersections may not be crossed?

Randall: This is an extremely complex and interesting question. I actually don't feel there are any absolutes here. I know there are those who feel that the white painter who made the image of a brutalized Emmett Till in his coffin had crossed a line. I didn't feel that way. I thought the painting tried to portray injustice, and I believe we all have a right to make that sort of statement in whatever genre. What offends one offends all. On the other hand, I respected the fact that Emmett's mother objected to the painting, and on those grounds alone felt it should not be shown. I think too of non-African women who decried female genital mutilation, and how that offended some African women. I was of the opinion that some things are just plain wrong, genital mutilation among them, and that we should take leadership on the subject from African women but that it wasn't appropriation of others—women or men, white or Black—to express our opinions on the practice. A white male poet impersonating a black sharecropper is always going to be problematic. But then, should Black actors not portray characters out of Shakespeare or others that were clearly not written for them? I think we run into trouble when we make absolute rules and judgments. It should be easy enough to determine what is disrespectful and what isn't. But I do think we must always cede that opinion to those who most deeply know what they're talking about, who are of course those who live the reality.

PF:I found the chapter about your wedding rings very touching. Thanks to the Obergefell decision, you were finally able to marry your partner Barbara in 2015. You write: "In the presence of family and friends, we legalized a relationship already twenty-eight years old.… Neither one of us has been able to fully grasp why the ceremony was so important to us…; we certainly don't favor state sanction over our own. Or why our rings are the talisman closest to each of our hearts." Can you reflect on the demands of family life (your four children, your various partners) and their impact on your creative and political work?

Randall: Barbara and I marrying legally in 2013 was indeed more moving to us than we could have imagined. I feel enormously fortunate to have Barbara in my life. We've been together for thirty-four years now, and our relationship just gets better. At the same time, I honor previous relationships, most of them with men. They gave me four wonderful children, ten grandchildren, and—to date—two great grandchildren. And much of what I lived with those partners remains valuable. I don't feel I must deny that just because the intimate part of the relationship failed. And I am happy that most of these men and I continue to be friends. I am particularly happy to have the offspring I have. Each of my children has made a life that gives them pleasure, and they are all giving back to society. They are their own people, which is the best I could have hoped for. I see this in my grandchildren as well, and now in my great grandchildren. They are all creative and courageous individuals. I just wish we didn't live on four continents!

PF:I know that many people your age or a little younger were attracted to what is sometimes called 'spiritual seeking,' often in response to their disappointments about the world of politics and social change. I don't detect that sort of interest in your work. What don't I know about your spiritual life?

Randall: I am a convinced atheist. I have my own spirituality that comes out of my relationship to nature and to art, but I don't find solace in any kind of religious expression. I respect the fact that many people do. I just don't. And so, when I speak of spirit I am speaking about experiences rooted in science, or the arts, but are none the less magical for that.

PF:I know that at times your life has not been easy. In fact, there were times when you and your loved one were in danger. Can you explain why your faith in democratic ideals has never wavered?

Randall: I'm not sure I know what you mean by democratic ideals. I'm not even sure that the best answer to people living together in equality and peace is to be found in what we call democracy. And then, the term itself is defined differently depending on what country we are talking about. Do we mean the kind of democracy we have in the U.S., where money buys political position, or the kind we find in New Zealand or Iceland, where women seem to have much more of a chance of political leadership, or the kind Cuba has in which money isn't part of the equation, but party control is? The recent presidential election turned out the way I wanted it to, but it was dicey for a while. Our democratic institutions ended up working, for which I am glad, but can we really say that the Electoral College is democratic? I think, to answer your question, what has never wavered in me is my conviction that we must struggle for justice and equality for all people, an inclusive vision rather than an exclusive one.

PF:Where did your enthusiasm for the masses come from? Or to put it another way, when did you know that you were going to devote your life to literary activism?

Randall: As a very young child I was the victim of sexual abuse on the part of my maternal grandparents. I disassociated and didn't remember the incest until mid-life, when I was able to retrieve it in psychotherapy. But I think that when one is abused, or suffers injustice, at an early age, one somehow recognizes injustice in its various forms and fights against it. On the other hand, I'm not sure that I would describe myself as devoting my life to literary activism. In fact, I don't like the idea that there is such a thing as "political poetry" or "political poets." To me there are good and bad poets. Good poetry can be about anything. Sometimes one expresses social or political ideas in one's poetry; sometimes one writes about love or fear or aging or other topics. In the broad sense we are all political beings, and so what we write reflects our ideas, beliefs, etc.

PF:You were an early American adopter of the Cuban Revolution. What drew you to Cuba? Did you know or suspect that the U.S. would turn against the Revolution with such ferocity?

Randall: Living in New York City in the 1950s, when Fidel Castro took power in Cuba in the last year of that decade, I was intrigued. Here was a tiny island nation standing up to the strongest country on earth! Even then, though, I wasn't surprised that the U.S. tried to destroy the Cuban revolution with every weapon in its arsenal. It had done the same in Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, and every other place that tried to free itself of U.S. domination and control. Later, living in Mexico, I had the opportunity of visiting Cuba twice, first in 1967 when I was invited to a small gathering of poets, and again the following year to the big Cultural Congress of Havana. On both those trips I was impressed by what Cuba was doing to improve life for its people, and especially by what was happening in the arts. In 1969 I was the victim of political repression unleashed by the Mexican government on those of us who had taken part in the Mexican student movement of 1968. I had to go underground and find a way out of the country, and I chose to take my family (I had four children by then) to live in Cuba. We lived there for the next eleven years, and my two oldest children stayed on after I left. This was the Cuban revolution's second decade, what I have called its glory years. Achievements were much more noticeable than problems, and transparency seemed to be the order of the day. Over the past ten or twelve years I have traveled to Cuba often, sometimes twice in a single year. I have witnessed the ongoing problems resulting from the U.S. blockade and also from internal mistakes on the part of the government and party. I have a critical view of the revolution at this point, even as I strongly support the revolution and decry the U.S. blockade.

PF:Your fake Mexican passport gets pride of place on the cover of your book; I love the story that accompanies it, especially the part about your nineteen-day trip (in disguise) getting from Mexico to Cuba (via the U.S., Canada & France)! How scary was it to be caught up in Mexico's Dirty War, something Americans don't know much, if anything, about?

Randall: It was frightening, as all such situations are. I feel fortunate to have escaped with my life. On the other hand, I am one of the lucky ones. Many have sacrificed their lives to fighting for a better world.

PF:Back in 2009, you wrote (in To Change the World: My Years in Cuba) that despite the immense difference in wealth between the U.S. and Cuba, the two countries seem to be going in opposite directions; Cuba was becoming more inclusive and humanist whereas in the U.S. life for many citizens was becoming increasingly more difficult and harsh. Do you think this is still the case?

Randall: Yes, I do.

PF:I read recently about a group of fourteen artists and poets being detained in an apartment in Old Havana by Cuban state security for over a week. How do you understand contemporary reports from Cuba about the harassment of artists and LGBTQ+ activists by the Cuban government?

Randall: I am critical of such harassment, deeply critical. Censorship takes many forms and is always bad. It leads to self-censorship, which is the worst kind. Sadly, some of the reports out of Miami about incidents of censorship and harassment on the Island are often exaggerated. I am sorry those who oppose the Cuban revolution so often feel they must exaggerate and lie when simply telling the truth would be enough. I don't condone injustice no matter where it takes place.

PF:You spent almost a third of your life in Latin America, supporting revolutionary governments when and where they appeared. What finally determined you to come back to the United States? Did you expect the kind of resistance you encountered? Most other people would have given up and returned to Latin America; what kept you going?

Randall: I was close to fifty when I returned to the U.S. in 1984 after having lived for twenty-three years in Latin America. It was time for me to come home. I needed my landscape, my language, my culture. I wanted to be close to my parents who were getting on in years. I did not expect to be ordered deported because of the content of some of my books. But when that happened, it never occurred to me not to stay and fight.

PF:Will the U.S. ever lift the embargo on Cuba? And if not, why not?

Randall: I hope so. It has never done anything but hurt the Cuban people, those who a succession of U.S. administrations have claimed they only want to help. In other words, it hasn't worked from the U.S. point of view and of course not from the Cuban.

PF:With the Trump administration, we've just experienced four years of libertarian plutocracy, seen its cruelties and excesses, and yet tens of millions of Americans continue to vote for the power of money. Why?

Randall: I would say we have seen neo-fascism at work. I think Trump appeals to a large segment of the U.S. population because he has distorted the truth to the point where these people believe the lies. The idea of "America First" has an appeal to those who don't understand that we live in a global world. Racism, sexism, homophobia, and xenophobia are attractive to those who need to put others down in order to feel strong themselves. I also think that the Democratic party machine—not the progressives in the party but the bureaucrats—must shoulder some of the blame; their arrogance over the years has been stunning. I want to say, though, that these people exist. They are our neighbors, coworkers, sometimes family members. So, we need to learn to listen and talk to one another. Trump is leaving a frightening legacy and we all have a responsibility in keeping it from poisoning us for years to come.

PF:Can we talk for a moment about the U.S. and its role in the world? Is the U.S., after four years of Trump, a failed state? We've seen the U.S. withdrawing from its post-WW II role in the world as the guarantor of the neo-liberal order? Has that shift made the world a more dangerous place or has it opened opportunities for progressive change? What have been the implications of that shift in orientation for Latin America?

Randall: It depends what you mean by failed state. In economic terms, the U.S. is certainly not a failed state, despite the fact that the Trump administration distanced the country from international organizations and treaties. On the other hand, the neo-liberal order hasn't worked so well, either. It certainly hasn't meant equality and justice globally. There is no doubt that the past four years have made the world a more dangerous place. In some ways, danger does create the possibility of progressive change. In Latin America, some countries have moved to the right while others have opted for a more revolutionary path. We've seen some genuine improvements, such as the successful struggle for a new Constitution in Chile, the return of a revolutionary government in Bolivia, and a Mexican president that has done a lot of good despite some serious missteps. At the same time, in Uruguay a progressive Broad Front was unable to hold onto power, and in Nicaragua a dictator continues to rule under the guise of "revolution."

PF:How do you react to the mayhem at our southern border? What should progressives be doing to stop the victimization of refugees and asylum seekers?

Randall: I believe we should be doing everything possible to make sure that those who want to come to our shores—legally or illegally—be considered fairly and treated with respect. Too often these people have fled situations that our government has promoted and sustained. The separation of families and forced sterilization of women has been unspeakable. The Dreamers, especially, deserve a chance at citizenship. Even when it states that its purpose is family unification, United States immigration policy has always served political interests. I live in a state that shares a border with Mexico and have seen firsthand the atrocities that are perpetrated on and near our southern boundary. I am not optimistic, though. Under Obama we also turned hundreds of thousands away.

PF: Do you think Biden will do a better job at managing U.S. interests in the world? Will he return to the Obama (neoliberal) status quo or embark on a more humane and progressive course?

Randall: There is no doubt in my mind that Biden will do a better job than Trump. No comparison. But I do not delude myself that Biden's policies will be the right ones. Advanced capitalism is advanced capitalism. The face will be gentler, less criminal. But will it be the face that makes us proud? Probably not. Having said this, I've never wanted a presidential ticket to win more than I wanted Biden/Harris.

PF:In the sixty-plus years you've been an active activist, what have been the most important changes in your life and in the world? What lessons can younger activists take from your life and work?

Randall: I make it a point never to give lessons to younger activists. All I ask is that they learn our history so as not to have to reinvent the wheel. Otherwise, I am listening to them.

PF: What haven't I asked that you want the readers of Poetry Flash to know?

Randall: Your questions have been interesting and challenging. I hope I've answered them to your satisfaction. I guess I'd just add, to quote Ad Reinhardt: "Art is art and everything else is everything else."

PF:One of the themes of My Life in 100 Objects is your excitement about meeting people who, after generations of oppression, are transforming their lives, creating spaces of greater freedom and autonomy. I have to say that I experienced an echo of that excitement, as well as a longing for greater freedom in my own life, not just a longing but a sense of real hope, which is often drowned out by the noise and mendaciousness of our consumer culture.

Randall: I'm glad you felt those echoes. At eighty-four, they are what sustains me.

PF: Thank you, Margaret, for reminding us of the importance of hope and solidarity with the oppressed.

Randall: Thank you, Lee, for bringing my words to the readers of Poetry Flash! ![]()

Lee Rossi's recent poetry book is Darwin's Garden: Studies from Life. His previous collections include Wheelchair Samurai and Ghost Diary. A staff reviewer and interviewer for the online magazine Pedestal, he is a Poetry Flash contributing editor and a member of the Northern California Book Reviewers; his poetry, reviews, and interviews have appeared in The Beloit Poetry Journal, Poetry East, Chelsea, and elsewhere. He lives in San Carlos, California.

— posted April 2021